As the threat of a humanitarian crisis grows, the world cannot turn its back on Afghan needs, regardless of Kabul’s new leaders.

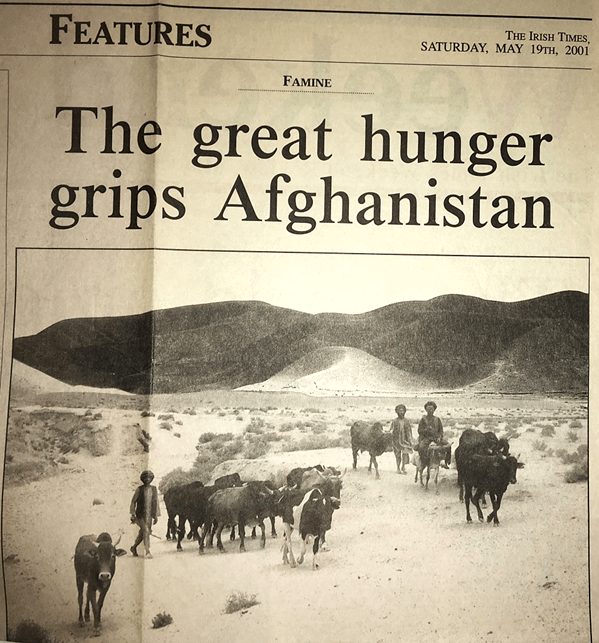

Two decades ago, my mother travelled through Afghanistan to report on a deadly drought and life under the Taliban. Reporting for the Irish Times, she wrote of the empty fields she passed, devoid of crops: “Across the vast plains of northern Afghanistan figures line the way — boys and old men — raising both hands to their mouths in a haunting ritual beseeching each car that passes by.” Today, in 2021, Afghans face a similar fate as a combination of severe drought and internal displacement has put intense pressure on diminishing resources.

Just over three weeks since the fall of Kabul to the Taliban, the world is still attempting to understand how the government and military collapsed so quickly. It did not take long for a blame game to start amongst Western leaders, as politicians sought to distance themselves from a series of failures in the run-up to the withdrawal of foreign troops. After twenty years of conflict since 9/11, however, the failings of Western intervention in Afghanistan cannot be confined to the last year alone.

While the geopolitical implications of the Taliban’s return to power continue to concern leaders and analysts alike, for ordinary Afghans left behind in the “graveyard of empires” it is the looming humanitarian emergency that is the most pressing issue.

Afghanistan before 9/11

Twenty years ago, aged nearly six years old, I was living with my family in Islamabad, Pakistan. When 9/11 happened, foreigners were urged by their embassies to evacuate the country and, so, my mother took me and my two older brothers to New Delhi, where we stayed for four months, while my father remained working as a journalist in Pakistan.

Earlier that year, my mother had travelled to Afghanistan by herself to cover the famine in the northern part of the country. As a western woman, she was mostly protected against the ruthlessness of the Taliban. Yet her short time within the country allowed her to witness life under their rule.

The first time she had been in Afghanistan had been years before, when the Soviets were leaving the country and the Mujahideen were still engaged in battle against them. Now, in early 2001, she arrived in Kabul on a Red Cross flight, naively thinking she would have permission as a journalist to travel.

The Taliban, however, were deeply suspicious of Western journalists. My mother was taken to one of their central bases where they interrogated her on her reasons for being there. Seated in a room with bare-footed Talibs and their guns propped against the walls, she convinced them that she was only covering the famine. Only after they were reassured that her reporting would not include any political focus, did the Taliban reluctantly relent and allow her to travel.

My mother travelled across the country to Maymana, in the north-west, accompanied by a driver and the Taliban’s chosen translator. Despite her initial reservations about the translator, he became chattier during their journey and told my mother that he was secretly educating his daughter at home. As they drove, they listened to music, and each time they came upon a Taliban checkpoint, they would hastily hide the cassettes. In her articles, my mother described the “tangled masses of black audio tape confiscated from drivers caught playing Western music in their cars” hung high above each checkpoint, acting as a warning to those thwarting their ban.

When I asked my mother whether she had felt frightened at any point, she described her first night in Mazar-i-Sharif; refused permission to stay at the UN guesthouse, she had been told to stay at a hotel located opposite the Taliban headquarters. She went off to socialise with other journalists and UN staff at their base but after a few hours, as the time for curfew set in, she had to make her way to the hotel.

The building was dark, and the electricity shut off. She was led up several flights of stairs by a boy and on each landing, they passed groups of bearded men sitting chatting. At the top of the building the boy showed her to her lightless room. She told me that it was only then that she had misgivings, as she sat alone in a dark, dingy hotel, surrounded by bearded men on each floor, across from Taliban headquarters.

When she left Kabul, just escaping the city as a sandstorm descended, her relief was immense. Years later, as she told me all this, laughing at her own recklessness, I listened in amazement. I also couldn’t fail to notice the similarities between the Afghanistan she visited and the present-day one.

‘Humanitarian catastrophe’

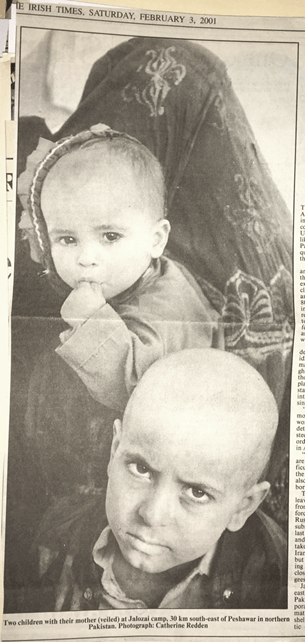

The famine my mother reported on was brought about by a terrible drought following three years of failed rains. Thousands were forced to flee their homes, adding to the huge numbers of internally displaced people who had already fled due to conflict. Acute malnutrition in children aged under five was becoming a serious issue.

Today, Afghanistan is facing a ‘humanitarian catastrophe’, as warned by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres. Nearly half of the population (an estimated 18 million people) require humanitarian aid, and more than half of all children aged under 5 face acute malnutrition over the next year. The direct causes, at least, are much the same as in 2001: drought, lack of crops and internal displacement.

Now that the US withdrawal is complete and the evacuations of both foreigners and Afghans have come to a halt, the world’s attention should shift to the humanitarian needs of those who remain in the country. Arguably, after two decades of military intervention by the US and its allies, the country should be left alone. Western powers, however, left behind many more problems than those they solved. Intervention, in the form of aid, must be continued.

Then and now

The similarities between the Afghanistan my mother visited and the one of today point to the grim realities experienced by Afghans daily, both then and now. Yet, in the years since 9/11, the country has indeed changed; the economy has grown, infrastructure has been developed and there have been significant gains for the rights of women and girls. Whereas in 2003, only 6% of girls attended secondary school, in 2017, this figure had jumped to 39%. Economic growth has slowed in recent years, however, and more than half the population live below the national poverty line.

The big question in recent weeks has been whether the Taliban have changed in any fundamental way. Their attempts to prove that they have changed and modernised show that they have; their understanding of media and good PR demonstrates a marked difference between the Taliban of the 1990s and the current leaders.

However, reports that are slowly emerging from the country (where many journalists have gone underground) appear to show that their media show is just that: a spectacle intended to garner attention and goodwill from potential donors. Human rights abuses — of journalists, activists, women — have been growing under Taliban-controlled areas in recent months and, since their arrival in Kabul, the evidence is mounting of further violations.

Moving beyond 9/11

Many hope that a country in which two-thirds of the population is under 25 years of age will not allow a regression to the Afghanistan of the 1990s. Yet, if we allow the West to walk away without a backward glance, then the few gains that have been made since 2001 will be lost. For both selfish and humanitarian reasons, we must continue to support Afghanistan with the critical aid needed over the coming months. To not do so would both be morally wrong and no doubt trigger further security concerns for the West, as the exodus of Afghan refugees grows and the situation within the country worsens.

When my mother travelled across the country in 2001, despite Taliban suspicion, her aim was to report on the plight of ordinary Afghan citizens. In 2021, while the geopolitical situation may remain fraught, global media must keep its focus on the humanitarian crisis now unfolding. The US withdrawal may be over but the ‘catastrophe’ is only beginning; now is not the time to turn our backs but, instead, to offer what aid we can.

As Afghanistan and the world turn a chapter, we may still hope that the next twenty years bring some positive change to a country that has seen endless hardships. In the coming months, scenes such as the one my mother witnessed, of famished boys and men desperately begging for food, must not be repeated. It remains to be seen how the Taliban will rule, but it is critical that their return to Kabul does not mean a return to an era in which the needs of millions of Afghans are forgotten by the outside world.

After working for Unicef and the International Crisis Group, Aisling is now an apprentice journalist with Euronews based in Lyon. When she is not studying or working, she enjoys running, being in nature or relaxing with a book. And a little fact for the Italian readers, her name Aisling (pronounced Ashling) means dream or vision in Irish Gaelic.